Hello everyone, I’m back with the third chapter in our exploration of the pillars for our vision of Stars Reach. Today I’ll be talking about the ones that get much more concrete about how the game works.

It’s been great to see the discussion of these pillars on the official Discord and MMO sites online!

The last big pillar starts out by describing the setting of the game. There’s a lot of stuff piled into a single overstuffed sentence, I admit! But we wanted to capture all the key elements that make the galaxy of Stars Reach what it is.

An Endlessly Explorable Fun Retro Sci-Fantasy Universe

The world is grimdark enough; our game will be visually appealing, brightly colored, and have a tone of optimism and enjoyment. It will accommodate melancholy, mystery, and even fear, but will do so within the overarching atmosphere of limitless possibility and player enjoyment. Around every corner will be new vistas, new things to discover, and new mysteries to unravel. New planets will be found (and lost), old secrets will be uncovered, and new content will be rolling out constantly, allowing players to find their own paths in a galaxy of infinite potential

There are a bunch of adjectives in there!

A lot of settings aren’t worlds. They don’t necessarily lend themselves to MMOs. A setting that is great for an MMO has to have variety, it has to have rich texture to it, and a degree of coherence and realism that a purely character-driven IP doesn’t have. We owe Tolkien a big debt for setting the template for detailed worldbuilding in service of an epic story.

But worldbuilding also has a “flavor” to it. The setting of Mad Max has thematic implications, and it’d be pretty darn weird to set the stories of, say, Studio Ghibli movies in a setting like that. (When they did their own post-apocalyptic thing, in Nausicaä, it was pretty different).

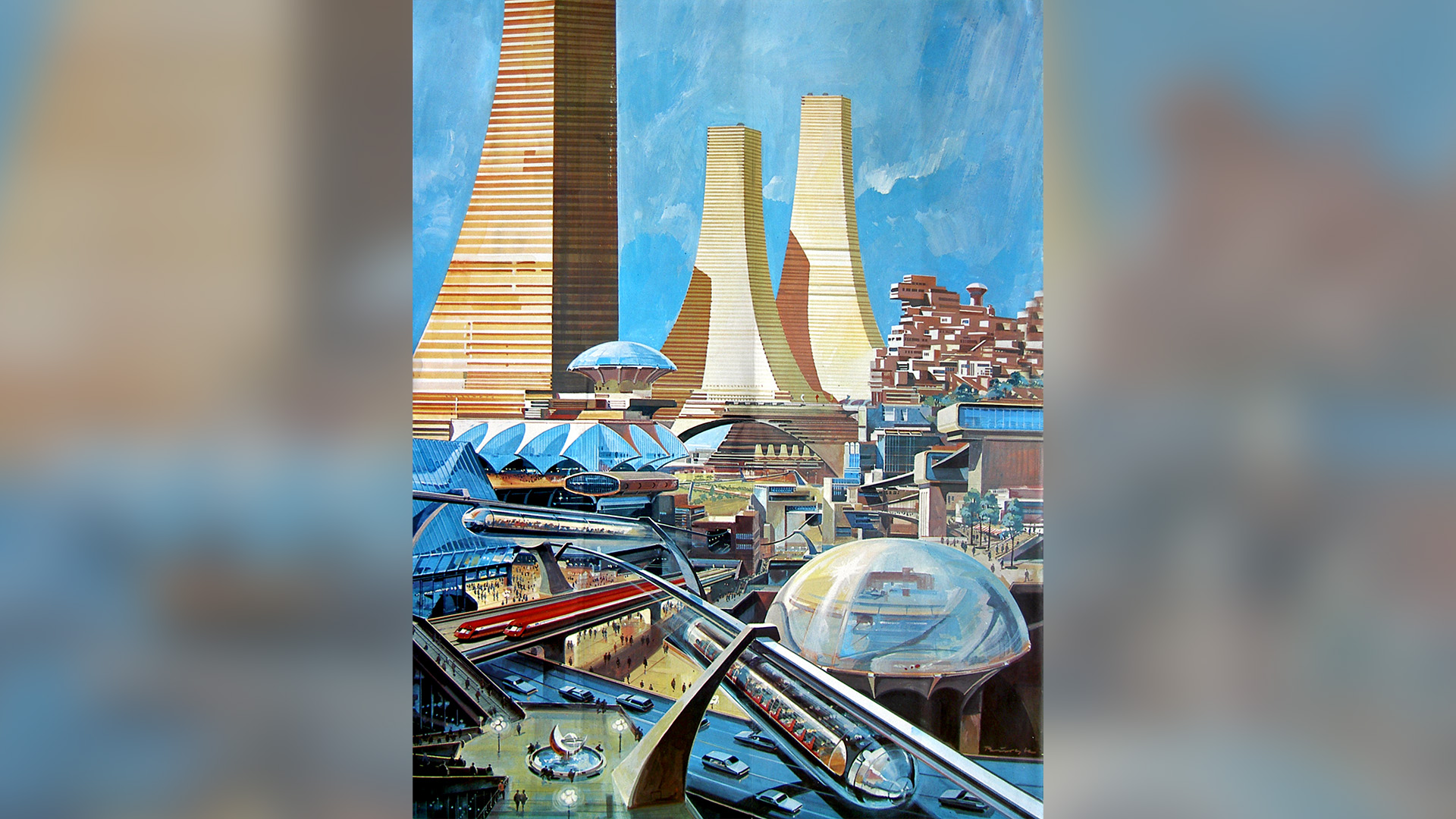

So let’s focus first on the “retro sci-fantasy” bit. Why retro? Why call back to older rocket-and-rayguns stuff?

It isn’t because we want to aim the game towards people old enough to remember that stuff from when they were growing up. And it’s not because we want to aim towards kids (a lot of that iconography has aged downwards as it has been used by toys).

Rather, it’s because we want to capture the spirit of that sort of sci-fi. It came from a period before, during, and post World War II where there was great enthusiasm about the power of science and the potential of humanity. Today, we see that retrofuturistic style used as a way to evoke the lost dreams we once had.

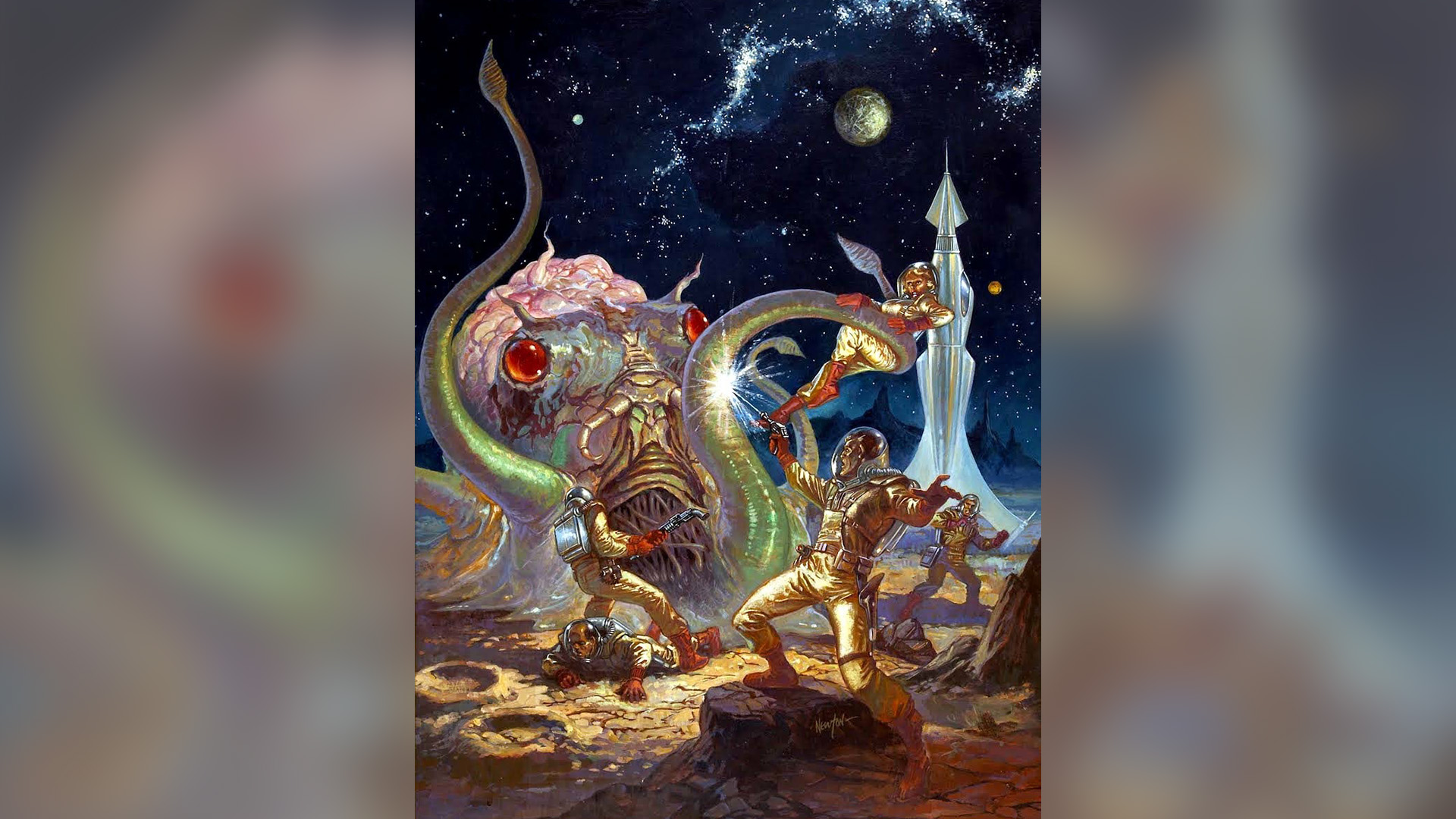

Here are a few images from our “mood board” of artwork that reflect that sense of possibility… but also the danger that can be out there.

Images from left to right: “Atomic Avenue #1”, art by Glen Orbik, Klaus Bürgle “Skyscrapers of the Future”, Don Newton “Unknown Worlds of Science Fiction” special #1, 1970s

After the war ended, print science fiction moved away from the sense of optimism (it took media SF on screen and in comics a while to catch up). The Golden Age gave way to New Wave SF, which was much more pessimistic about humanity and the future. Ever since, science fiction has been much more ambivalent about technology. Even the premier space opera of our time, Star Wars, is gritty and dirty.

Ultimately, that ties back to the core themes of our game and our lore:

Stars Reach is a game about hope and optimism. The real world is grimdark enough. We want to capture that sense of possibility that was present in Golden Age sci-fi, that sensawunda (“sense of wonder”) that it evoked.

That doesn’t mean we have to shy away from serious themes or dark elements in the storylines. We need a world that can encompass many sorts of stories. But it should be presented in an overall spirit of optimism.

Humor is fair game, but we lean towards wit, caricature, and gentle humor, as

opposed to cartoon, slapstick, or “easy” dad jokes. This is not a comedy game.

It’s a game that takes things lightly.

The lore really deserves its own blog post, because a lot of thought went into it. It’s designed to provoke questions, and in keeping with the other pillars, it’s meant to be easy to approach but offer depths that aren’t apparent on first glance.

The game will have deep lore.

As Tyrion put it at the end of Game of Thrones, stories are what hold us together. Tribal identity is driven by culture, and culture is driven by stories. We want to create a new tribe, the players of our game. We can unfold discoveries over time, and drive the sort of tapestry of complexity that long-lasting IPs have, a web of characters and motivations that generate fan fiction and cosplay and the like. These things are what create a long lasting fandom.

The central theme of the game is that our player species have plundered and destroyed their homeworlds as they have clawed their way up to the brink of interstellar civilization. Now, these species have been given a second chance: a galaxy of terraformed worlds on which to build their future.

Will they learn from the lesson of the fate of their various homeworlds? In order to support this theme, responsible shepherding of these inherited planets must be rewarded by the game, and thoughtless plundering of them should be punished.

Among the things that we want to make sure the lore represents are an understanding of the grand sweep of history, themes of cross-cultural communication, how one deals with a Galaxy where a genocidal species basically swept thousands of planets clean, a feeling of uncovering a deep past… one of the central mysteries is, where did the Old Ones go and why did they leave? We don’t know whether they annihilated themselves, decamped to greener pastures, or were exterminated by something even more terrifying.

So all in all, Stars Reach is upbeat, optimistic, and colorful; yet capable of weighty themes and strong characters. It is meant to project hope, and it is also a game that winks and nods at itself and the tropes it uses. If I had to sum it all up, it would be we’re going into space, and it’s going to be awesome.

Now, if you’ve followed the reception to SR online, you probably already know that the graphics are a bit controversial. I’ll restate again that we aren’t at all done with the visual style. But I also won’t lie, nailing an art style for the above is challenging. It ties back to whether the basic presentation is conveying that tone but also stretches to accommodate all the tonal variety we want in the lore and setting – and also reaches the audience we want.

One of the challenges with a hyperrealistic style is telling all the games apart. As rendering capability has increased, realism is starting to get… kind of boring. From a business standpoint, we need to stand out in the market. We also need to keep costs down, and our technology that allows us to stream content down on the fly works more cost-effectively with less load in terms of highly detailed textures. But lastly, high realism tends to tell broader audiences “this game is not for you.” It signals to people that the game is complex, unapproachable, and often specifically chases away women players.

The game will be welcoming and fun and beautiful.

Edgy may drive core audiences, but most mass market things are fairly sunny and brightly colored. If we want to drive retention, we need the experience to not be stressful; an escape more than an ordeal. If we want people to live in the game, we need to make it feel livable.

I vividly remember two great examples of this from long ago – when World of Warcraft came out, and when Dark Age of Camelot came out, they both felt immediately more colorful and welcoming than Everquest was.

This is a hard line to walk. When we were doing early concept art, we actually developed a “realism to cartoon” scale, where we made sketches of a human avatar’s head, in styles ranging from kids’ cartoon through to realistic, and told ourselves, “never fall below a 7 on this scale.” But it’s a long way from sketches to in-game art, and we still have more work to do.

This leads to a set of specific goals for the art style of the game:

-

- Do to grimdark sci-fi what World of Warcraft did to grimdark fantasy.

- Bright and colorful — a place you want to be.

- High beauty, not high fidelity – by which we mean, it is more important that the environment be attractive than it be super high res textures and realistic rendering.

- It can be fun and even funny, but archetypes, not cartoons.

- Familiar tropes that serve as “anchors” for players’ imagination, because much of the best visual design leans on things that are already familiar, then add a twist – rather than going all out weird with something that people can’t relate to

- Strong silhouettes and iconic forms that can move across art styles.

- Influence from caricature and anime, for a contemporary look.

- Iterative development: we test our stuff and see that players respond.

You can be sure that as we continue to iterate the art style, we’ll be doing a lot of that last one with you all!

Our last pillar is all about gameplay.

The game will constantly generate new content.

It is expensive to make content. We want to enable players to create as much as possible, and we want to enable the game to create as much as it can as well. It has to be constant, because we want players to always want to learn about what’s going on. We want them to feel like it’s something that stays fresh and evolves and makes them want to check in regularly.

Now, this doesn’t exclude content we create. But that’s sort of the default assumption these days in design: that the designers will populate all the content. Designing for the game itself to drive emergence doesn’t mean that we abdicate our responsibility to create engaging content. But it does mean taking a look at every single system to ensure that it isn’t reliant on that.

From this emerged a whole bunch of pretty specific principles which shaped the game design very powerfully.

We decided that Collection, Crafting, Settlement, and Combat were the core activities of our game. This wasn’t arbitrary, either. It was driven by the audience we are after, which is a large one, and a diverse one in the sense that it is made up of players with varied gameplay preferences but who all like existing in a sandbox together where they interact.

This then also implied two big things:

-

- The entire game economy is player-driven.

- Combat is opt-in, and not at the core of the game loop.

To many players, these two things may feel like a marginalization of combat. The fact is that combat usually marginalizes everything else, so every once in a while turnabout is fair play! I was wondering online a while back on Reddit, “when exactly did we start calling everything else you do in an MMO ‘life skills?’” The default current of MMO design usually puts combat at the center, and relegates other ways to play to “side games.”

Everyone always feels like their preferred way to play should be dominant, and can even get pretty resentful of seeing other ways to play present. But there are good reasons to interweave everyone more.

We want to put Community First because MMOs are about other people. I often describe virtual worlds as “be someone you aren’t, somewhere that you can’t be, with others.” That’s the heart of the unique offering of MMOs. You can get individual bits of that sentence elsewhere, but there’s something magical that happens when you get all three from one experience. And it leads to a few more goals:

-

- Player-driven economy fostering social ties – because each different play to play the game can be related to the others via the goods and services that playstyle outputs.

- Similarly, having multiple guild types and multiple guild membership also helps foster strong ties. Basically, a common pattern that we see (and a common mistake, we’ve come to realize) is trying to make human relationships one-size-fits-all.

- “Increase communication bandwidth.” Chat, emote animations, etc, should be very important, because the higher the bandwidth for emotion and humanity to pass through the game, the more likely players are to behave, because it’s easier to recognize the people on the other side of the wire as being people like yourself.

Of course, that means you have to recognize that it takes all sorts of people playing in their own ways to build a world. That sort of diverse playerbase is very different from chasing a super narrow audience of specialists in just one way to play. The bet we are making is that the range of playstyles in one game will appeal to people who get tired of one-note play. If you get bored of one way to play, you can go try another.

We think of that range of play in a couple of ways. We have to support diverse sorts of players – different age ranges, genders (a lot of games chase away demographics through their choice of art style, as mentioned above), ethnicities, and so on. We also need to support different playstyles; we have used both Quantic Foundry and Solsten models to think about our players at different stages of the game’s development.

And lastly, we need to level the playing field some between new players and old pros. The power accumulation curve of most MMOs results in friends being unable to play together as soon as one of the members has more or less time to play than the others. MMOs have long recognized this problem and built design hacks into the system that basically “undo” you advancement when playing in mixed-level situations. The first one of these was “sidekicking” in City of Heroes in 2004, but nowadays we have level scaling and other approaches, all of which are fundamentally about ignoring the level system that the game is designed around.

Since we favor horizontal progression, where instead of “numbers go up” we have “number of commands goes up,” we can avoid this issue. In our game, your hit points won’t go up noticeably. And you will do more damage not because you leveled up or your gear got better, but because you compounded tactics together that you unlocked with skills.

So, that (finally) finishes the series on key pillars for the game. I hope you found it an interesting glimpse behind the curtain on how we try to wrangle a huge project like Stars Reach into something that a team can wrap their head around.

That’s it for this week, but I’ll see you around the Discord, or Reddit, or wherever your favorite theorycrafting community is, and if you want to talk about these pillars, I’m always up for it!